Book cover of Daring to Look

One day when I visited my local library I saw this book, National Gallery of Art Master Paintings from the Collection, displayed near the entrance. I decided to check it out and spend some time with it, and I’m glad I did. I have visited the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., on several occasions so I’ve been fortunate to personally see some of these paintings. But it was still great to view them at my leisure while at home, granted in a smaller format, though this is an oversized book at approximately 9x12 inches. One big benefit the book has over the museum is the text. There are a number of short commentaries on many of the specific works with plenty of details about the artist and their life.

The book begins with a Director’s Foreword by Earl A. Powell. It’s very short but provides lots of background about the museum and its collection. It’s a very young art museum when compared both to other museums in the US and especially when compared to many of the well-known galleries in Europe. It opened in 1941, founded by Andrew W. Mellon, and began with his collection of 121 master paintings. From then on it has benefited from many donations, both of artwork and of funding to purchase artwork. This book contains roughly 400 paintings from their collection, selected by John Oliver Hand, who also wrote the commentaries.

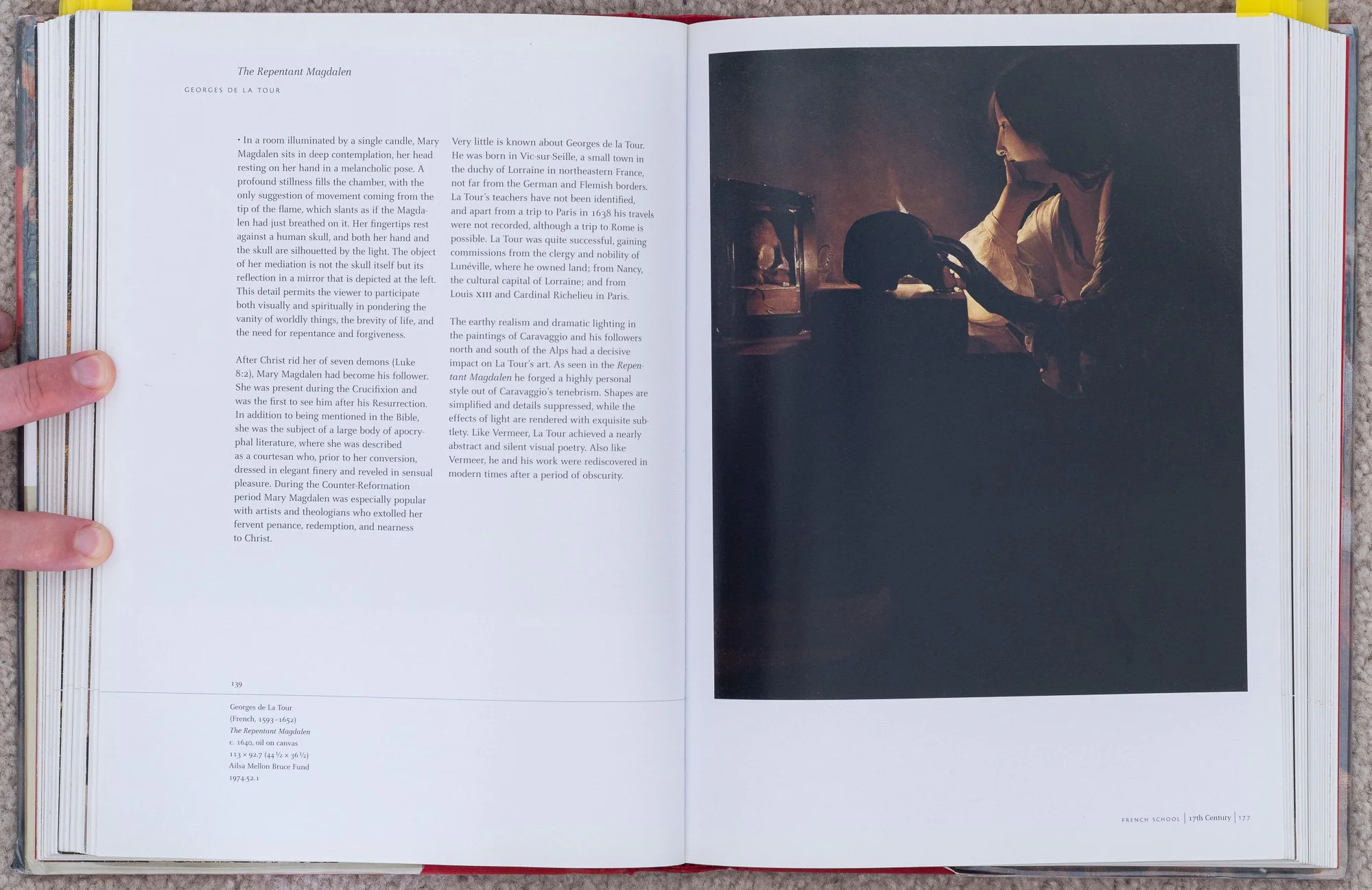

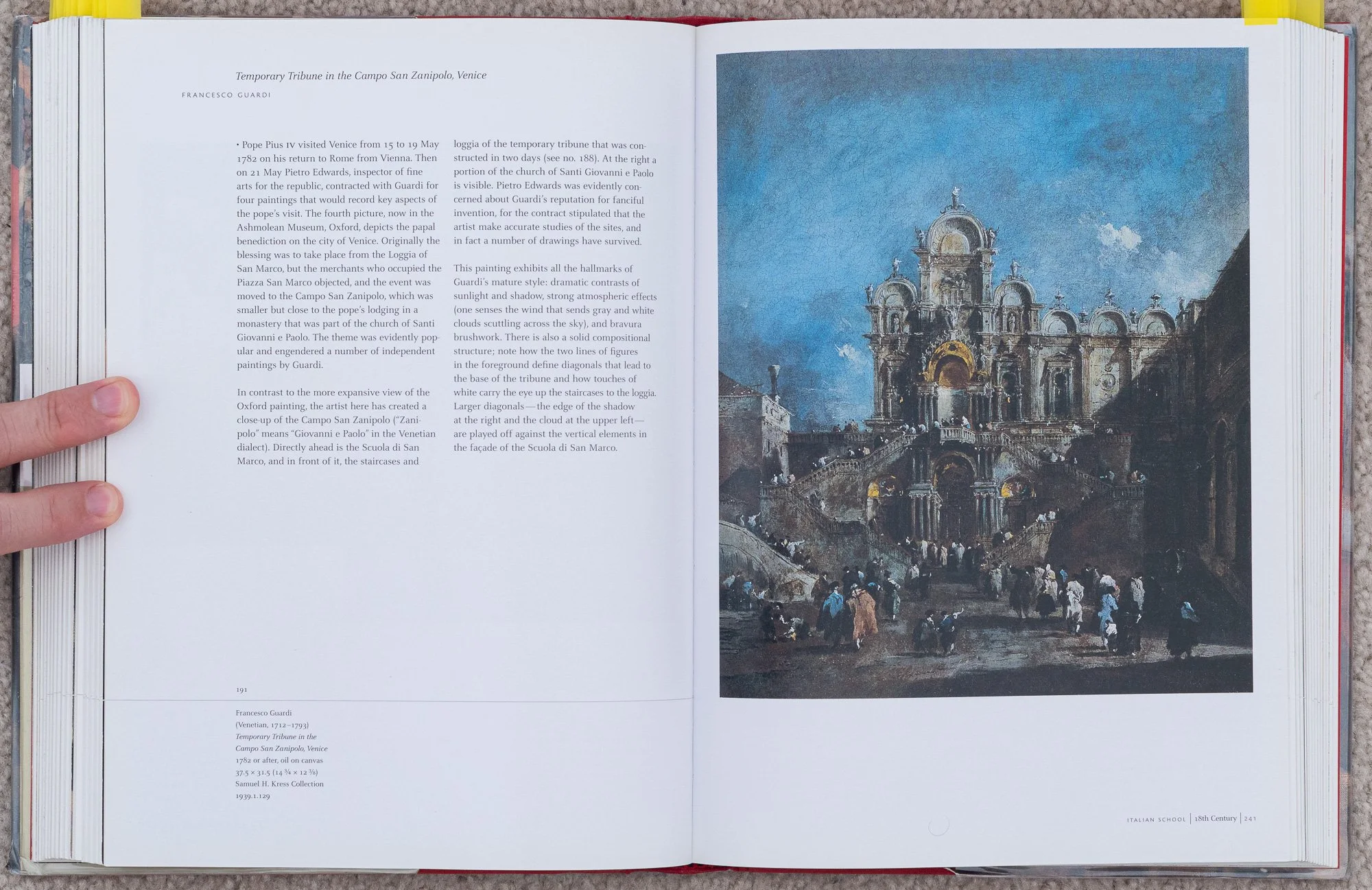

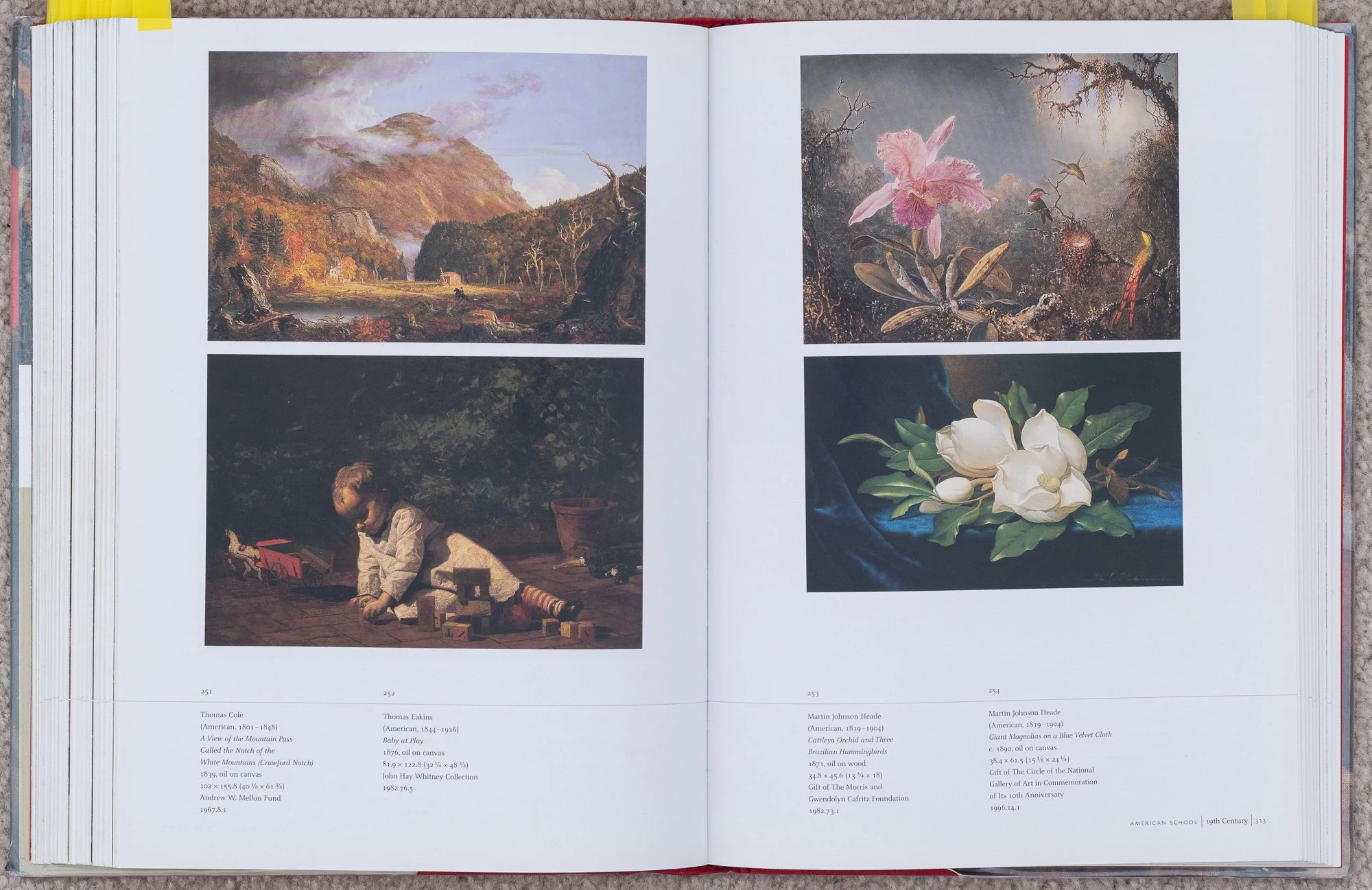

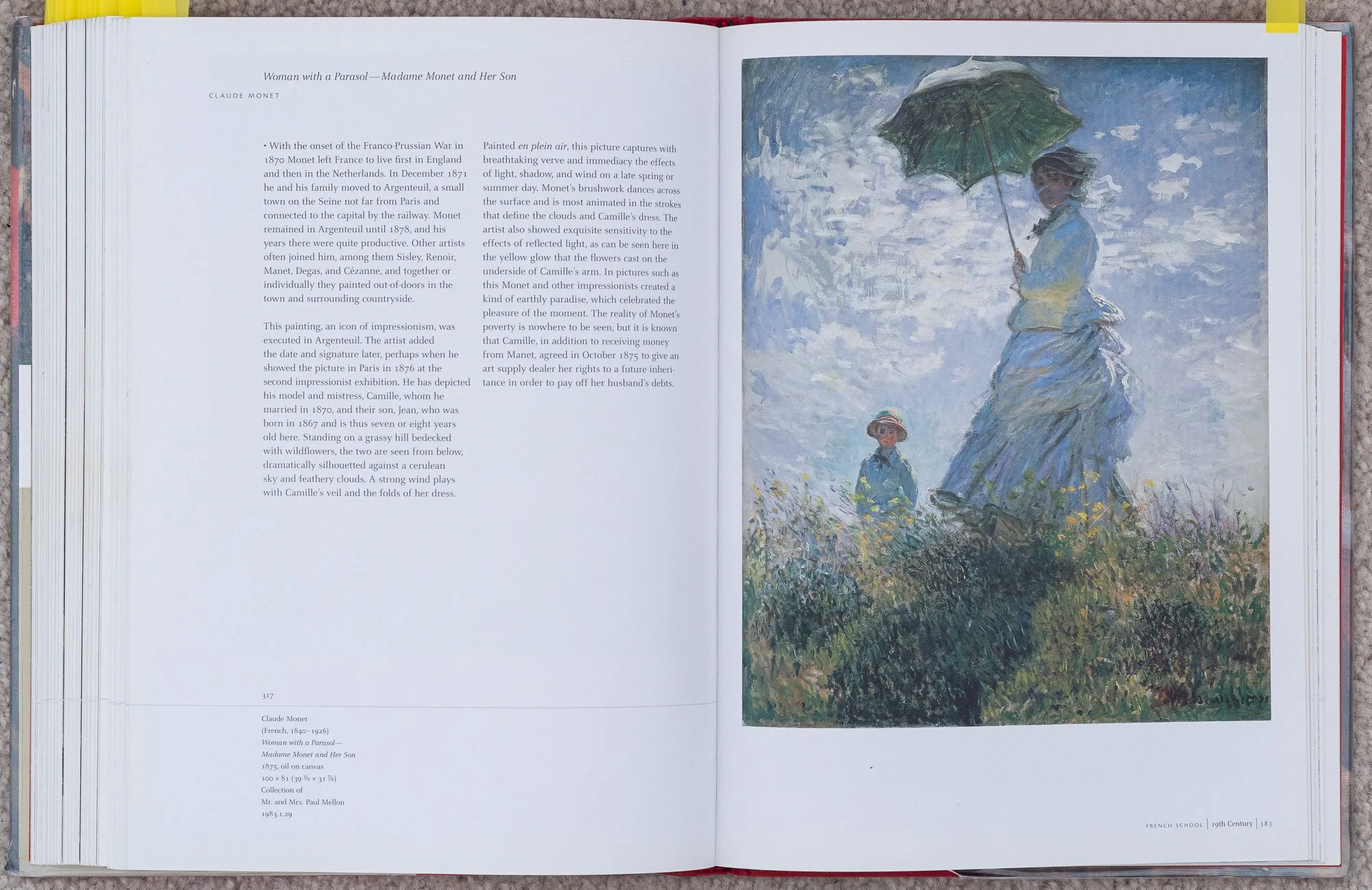

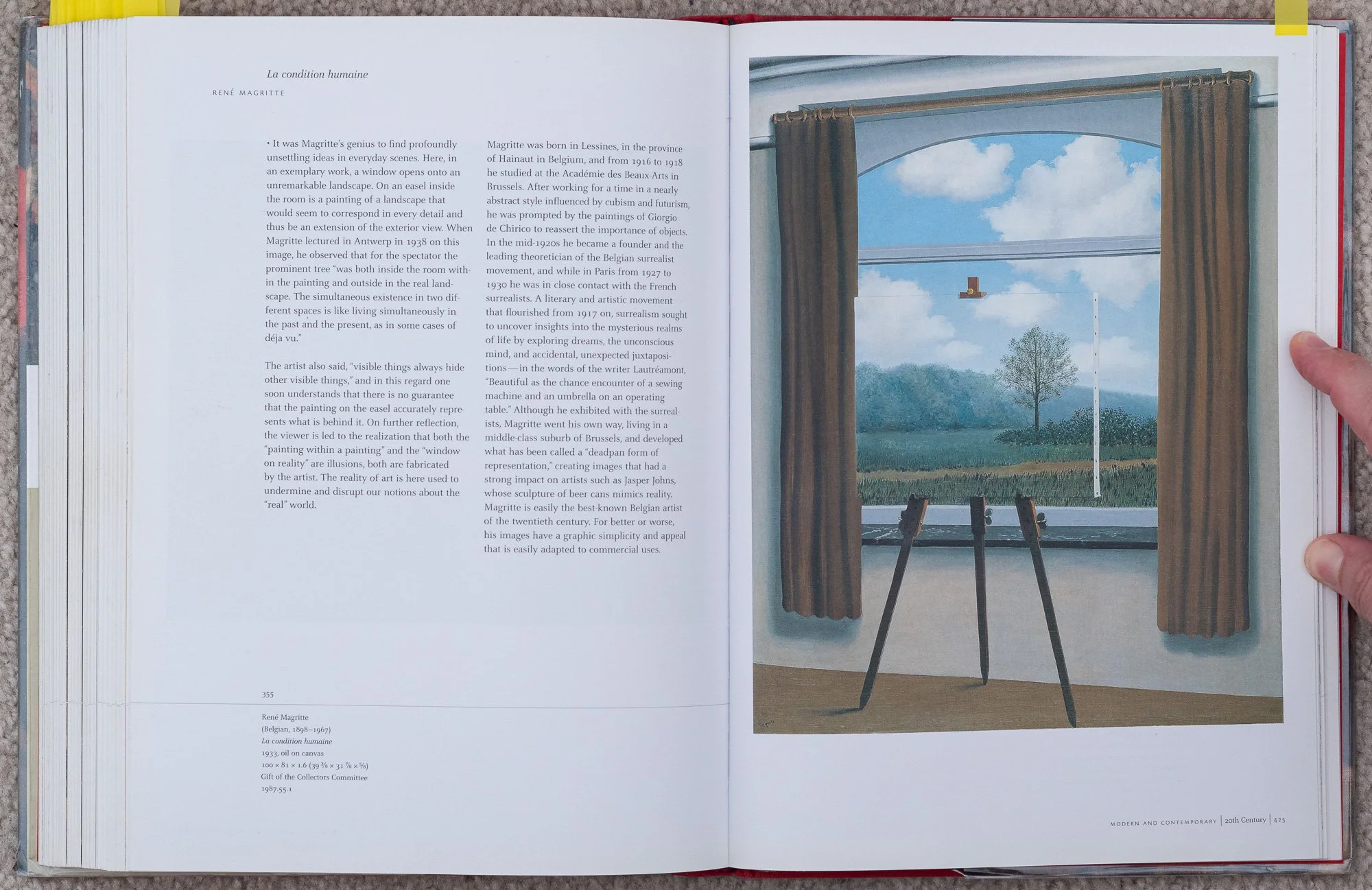

The majority of the book contains the artwork, with some pages featuring a single piece of work, others with multiple paintings on a single page, and in some cases with some detailed portion of a painting blown up to a full page size. Each painting is accompanied by details such as title, artist, date, media, size, and donator. Many are paired with a commentary providing lots of extra details and background.

The book is organized by century, from the 13th/14th centuries to the 20th century. Within each of these sections the paintings are sorted by schools or art: Italian, Netherlandish, German, Hispano-Flemish, French, Spanish, Dutch, Flemish, British, American. I found it fascinating looking for stylistic similarities within schools and differences between them. I also found it fascinating studying how the styles changed over time. And as I found when visiting the actual galleries, there were specific styles and time periods that most appealed to me, and those I generally found least appealing. Being a photographer, I very much appreciated studying how each painter used light within their compositions, how they chose to apply highlights and shading. Some of these paintings really do achieve life-like quality, whereas others intentionally avoid that, using more impressionistic or stylistic techniques.

I struggled to choose a small subset of the 474 pages to show here as samples of what you can expect within the book. Naturally, I leaned towards works I found more appealing for one reason or another. This does mean I haven’t included many modern art pieces, so my apologies if that’s what you’d rather see more of. I obviously had to skip over so many fantastic pieces.

This book is well worth checking out if you can find a copy. And of course the museum is also worth visiting. I’d be curious to read your thoughts on the book, museum or artwork in the comments below.

Do you enjoy these posts?

Sign up to receive periodic emails with updates and thoughts. Don’t worry, I won’t spam you. And please consider purchasing artwork or products from my online store, and using my affiliate links in the sidebar to the right when shopping online.

I appreciate your support!